Margaret Huang ’19 came to law school looking for tools for change. Inspired by seminal Supreme Court cases like Roe v. Wade and Brown v. Board of Education, Huang set her sights on finding her particular path into change agency. At the time, law school seemed like the best way for her to acquire the skills to combat systemic racial and economic inequalities. However, by providing new frameworks for analyzing problems, law school has complicated her theory for how change happens.

Margaret Huang ’19 came to law school looking for tools for change. Inspired by seminal Supreme Court cases like Roe v. Wade and Brown v. Board of Education, Huang set her sights on finding her particular path into change agency. At the time, law school seemed like the best way for her to acquire the skills to combat systemic racial and economic inequalities. However, by providing new frameworks for analyzing problems, law school has complicated her theory for how change happens.

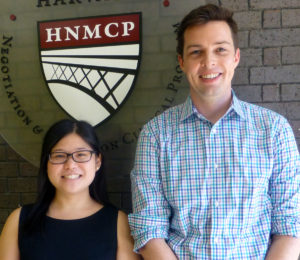

HNMCP: When you were a student in the Negotiation & Mediation Clinical Program (HNMCP), you worked on a project with the New Hampshire Judicial Branch Office of Mediation & Arbitration, which oversees alternative dispute resolution programs in the state. Your project looked at the use of alternative dispute resolution models in the family division specifically, focusing on the process for handling re-opened divorce and parenting cases. But this wasn’t your first hands on experience with clients, was it?

Margaret Huang: In undergrad I volunteered as a telephone counselor at the Women’s Law Project. My role was to provide legal information and referrals when people called in with their stories. It was the first time that I truly began to understand how interconnected problems in people’s lives were. Divorce, parenting, domestic violence can affect safety, shelter, and food insecurity, as well as be affected by them. This experience helped me in thinking about the project with the New Hampshire court because it gave me a deeper understanding of divorce and parenting disputes.

HNMCP: What was it about HNMCP that made you choose it for a clinical experience?

Margaret: I wanted to do more work in alternative dispute resolution. The Negotiation Workshop and the Harvard Mediation Program influenced the way I looked at disputes. These experiences taught me that sometimes the truth can be impossible to determine, but they also gave me the tools to figure out how to move forward despite that. And then the clinic, HNMCP, does a good job of providing a framework in which to analyze how individuals act within a system. By figuring out how a system influences the people who are within it (e.g., through the options it provides, or the difficulty or ease of taking a certain path), we can figure out how we might shift things for a different experience.

HNMCP: How did you see this fitting in with the work you want to do after law school?

Margaret: Like many people at this law school, I feel an urgency in the work of reforming the criminal system. The criminal system is both a result of, and a force in, perpetuating trauma and racial and economic injustice. But because of the power that prosecutors have, I also believe that to implement effective change, we need progressive prosecutors. After law school, I am going to the New York City Law Department’s Family Court Unit to work as a prosecutor in the juvenile court system, with the diversionary programs that exist there, and its focus on rehabilitation. When I worked there last summer, I learned about all the alternatives to placement programs like job training, family therapy, etc. to help keep a child from going back through the system. I think it’s a good model on how to handle juvenile cases and I am thinking about how can it translate into the adult system. No matter how gung ho individual prosecutors are, at the end of the day the outcome is supposed to be the least restrictive. Understanding systemic models better will help me move into policy work at local and state levels in the future.

HNMCP: While respecting client privilege, what were some rewarding and challenging experiences you had in your clinical work that you felt helped you move forward in your growth as a lawyer?

Margaret: I was amazed at how the people we worked with in the New Hampshire Court System were so forward-thinking. I feel like the way law school teaches the common law means there is a focus on the past, a mentality of ‘we do things this way because this is the way we’ve always done things.’ But the people we met in New Hampshire were constantly innovating and trying new models to help the people who go through their system. They were so inspirational!

The most rewarding part of the clinic was when [my project teammate] Michael [Haley] and I presented our findings and recommendations to the court administrators. Our analysis was objective, presenting both the positive and negative things that we had seen, but the court administrators were excited about our findings and seemed energized to start fixing some of the problems that we had found.

We did have challenges. As part of the project, we spent time calling folks who went through the New Hampshire system to get stakeholder feedback. Not all of them were very happy that their number had been given to us and one guy called around 15 times in 10 minutes to complain.

HNMCP: So you had that on-the-ground learning of interacting with folks who had challenging experiences in the system and you were the one who had to talk to them and take that blow back.

Margaret: Yes. This is one of the places we got support from our supervisor. I learned a lot seeing Rachel [Krol] talk to him and calm him down. It was so admirable.

HNMCP: You also participated in the Harvard Mediation Program (HMP), a student practice organization. What was it about alternative dispute resolution as a discipline that attracted you to spend so much of your time in law school focusing on these skills?

Margaret: It was learning that 90% of cases settle out of court that made me want to learn about ADR. I stayed with it because of the experiential learning model and the practical skills I was receiving. Black letter law classes teach one set of skills, so studying ADR gave me that continued learning.

HNMCP: You started in HMP your 1L year, served as Training Director your 2L year, and by your 3L year you served as co-President (along with Laura Bloomer). What are some important leadership lessons you’ll be taking with you into your career?

Margaret: One of the gifts of being co-President was being able to see the organization in the long term. It also gave me the opportunity to tackle some of the problems I saw as a 1L. As Training Director, I had the ability to address issues, make changes right away, and move forward quickly. But as co-President, of course, I had to run things by the Board and Staff, and know that I might not see changes before I graduated. Hearing [Advisory Board Member] Florrie [Darwin] share with me the growth she’s seen in the organization over the years, helped me understand that despite the fact that I could not immediately see the progress the organization was making, the changes Laura and I tried to implement might have an effect in the future. I also learned that working with colleagues who are committed and caring makes a huge difference.

HNMCP: What did you learn about yourself in your work in HNMCP and HMP?

Margaret: In both HNMCP and HMP I learned how to receive feedback, which is much harder than people acknowledge. But I needed to acknowledge where my weaknesses were in order to improve. So now I hear feedback as not about what’s wrong with me, but where I can get better.

I know I have said this a lot already, but HNMCP and HMP has influenced how I think about change. I used to believe that it was extraordinary individuals who were change-makers. Not to diminish the extraordinary things these individuals have done, but the picture is much more complicated. I now understand that because ADR teaches people how to analyze situations as stakeholders with their interests and agendas, I can see that change happens when some stakeholders agree on a solution that fits their needs. By using this framework, one can make change by influencing stakeholder agendas, by empowering certain stakeholders, finding creative solutions, and countless other possibilities.

I’ve also become more aware about how people make choices in a system. I was at the Prison Abolition Symposium that the Harvard Law Review put on earlier this year, and one of the speakers, Angel Sanchez, said something that really resonated with me. Paraphrasing, he said, “we should allow people to be normal.”

We should allow people to be normal. How can we construct a system where people do not need to be extraordinary to “make it?” How do we construct a system where people are allowed to make mistakes?

HNMCP: How have you found these skills translating into your own life?

Margaret: I’ve become a much better active listener [laughs]. In law school, we’re taught to provide solutions when people come to us with problems, but sometimes that’s not what someone needs. Sometimes it’s better to just acknowledge what’s going on and help them figure out what is the best solution for them.

HNMCP: Anything you want to add before we go?

Margaret: A big shout out to the 5th floor of Pound Hall [where HNMCP and HMP have their offices] for being so welcoming!