Dispute systems design, when done well, emphasizes thoughtful, intentional engagement with stakeholders in order to develop robust conflict management systems. Is this approach useful during an acute crisis?

A few days ago, a friend who works in a state court system sent the following email to me and a number of colleagues in the field of dispute systems design (copied here with permission):

A few days ago, a friend who works in a state court system sent the following email to me and a number of colleagues in the field of dispute systems design (copied here with permission):

The courts desperately need you, facilitators and dispute system designers, to be working with them right now. It doesn’t matter if you have students or if you have a lot of time. Any ways you can assist in designing the new methods by which courts will (and are) resolving disputes to ensure access to justice, the better. This is not just about offering more mediation, but about rethinking how we structure our justice system writ large. This is our one shot to redesign this system all at once; we need you.

There were two aspects of this message that were instantly clear: First, the magnitude of the challenge to courts is enormous and growing. The existing systems the courts have used up to this point to administer justice have been fundamentally ruptured, which creates an immense challenge – but also a unique opportunity for dispute systems designers to fill the void.

Second, the need is immediate. It is important for dispute systems designers to get involved and help without delay, even if the circumstances and level of resources are far from ideal.

The urgency expressed in the email got me thinking about the role of order, method, and time in the practice of dispute systems design. There is a way in which DSD honors and elevates the slow: from an academic standpoint, stakeholder assessment is a thorough and deliberate process of asking nuanced questions; there may be multiple rounds of assessment in order to sweep in all stakeholders; analysis of the data is likely to be complex and require follow-up or further inquiries. DSD is aided by, and indeed, reliant on, reflectiveness and continual looping-back to check the integrity of the process.

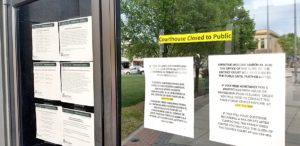

By contrast, the pace of change stemming from Covid-19 has been anything but slow. Each day seems to bring on a relentless march of compounding and increasingly dire challenges, not only on the healthcare front, but also within the countless settings that are feeling the ripple effects: courts, schools, housing authorities, individual homes, small businesses. People—and the systems in which they operate—are feeling pain, deeply and daily.

Herein lies the question for dispute systems designers: How can we reconcile the core value of building a thoughtful and inclusive process with the need for immediate action? And when it comes right down to it, how can any dispute systems designer stubbornly adhere to complete process integrity, when lost time could be measured in human life? In the declining balance of a family’s savings account? In deeper and more intractable entanglement in the maw of the legal system?

In some ways, the very notion of a “system” is resistant to something reactive. Systems are in place, in part, as a way of controlling and planning for the “unknown unknowns,” and maximizing the chances that challenges will be handled in a thoughtful and deliberate way—a way the system has planned for and prescribed—when an acute need arises. System design is prophylactic by definition, intended to anticipate eventualities and account for possibilities. While they can be tailored, systems are not always known for being particularly agile. And at the same time as a systems approach promises comprehensiveness, it is also potentially cumbersome: a truly inclusive system design in its classic form requires a broad base of stakeholder input, thorough analysis of the themes that emerge, and a distillation of all of that data into discernible findings and recommendations. In the current moment, it can feel hard to translate actual activities in the DSD process: What does stakeholder assessment look like for a group of emergency room nurses protesting unsafe working conditions? Can school systems afford to “test” recommendations when there’s no ability to reconvene students until next fall (at the earliest)? When nearly all interaction across the board has been migrated online, is it reasonable to expect stakeholders to participate in additional phone conversations or online focus groups? What if stakeholders struggle to find reliable internet access?

When experiencing the symptoms of a broken or dysfunctional system, it’s tempting to run straight to problem-solving. It’s logical to want to identify and implement action steps, skipping over a thorough understanding of how challenges are manifesting, what the myriad of causes might be, and what variety of approaches might be taken to tackle the problems. This shortcut to specific solutions is, in many ways, anathema to the model underlying our work. Stakeholder assessment alone takes time, and that’s probably just how it should be.

Fortunately, the same tools and levers that can make dispute systems design potentially cumbersome and even overwhelming can be viewed another way. DSD’s core tenets also enable practitioners to be agile, responsive, and action-oriented. For instance:

- The emphasis on evaluation and feedback loops that constantly check recommended solutions against how things are playing out in practice allow for adjustment and make it “safer” to try out different approaches;

- The tethering of solutions to what stakeholders are saying and experiencing roots the recommendations in the felt experience, and provides accountability to the dispute systems designer by inextricably linking her to the reality on the ground;

- The out-of-the-box and expansive thinking about who is a stakeholder to any given system broadens the horizons of potential solutions by uncovering perspectives that may previously have been forgotten, ignored, or just not considered important.

In many ways, taking action in the face of imperfection is at the very heart of what we do as dispute systems designers. We coach our students and clients to engage with conflicts as they are, rather than wishing or willing them away—as uncomfortable as that may be. Perhaps what this moment demands of dispute systems designers is a further embrace of this core principle of our work: to put ourselves and, indeed, our practice “on the line” in service of trying to make a difference at a moment when systems thinking is desperately needed. To be open to the possibilities that our “ideal” process may be flawed, that we’ll make mistakes, that not all stakeholders will be on board with or feel ready for a systems design process, that the reality on the ground will point to the need to modify what we teach, that we’ll offer ideas that ultimately don’t work. There is fear and risk in those possibilities. But my colleague’s words suggest the cost of inaction.

Dispute systems designers are, in this sense, ideally placed to play a role in this particular moment, when systems need to be reimagined. And in order for dispute systems designers to confidently wade into the enormous challenges and opportunities now presenting themselves, we will all need to find a way to avoid making the perfect the enemy of the good.